| ASLEF | BBC-NEWS | BLACK LIVES MATTER | CITIZENS ADVICE | DEMENTIA UK |

| WHICH | DEPARTMENT FOR WORK & PENSIONS | EUROPEEN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS | END FROZEN PENSIONS | FORTUNE & FREEDOM |

| LOCAL COUNCIL | LOCAL COUNCILORS | HOTLINE | ILZ |

| MILLION WONAM RISE | UK DEBT CLOCK | NATIONAL EDUCATION UNION | NHS |

| ROYAL COLLEGE OF NURSING | RESEACHING REFORM | RMT – DEFEND RAIL | SAMARITANS |

| STRICKES | THE CO-OPERATIVE BANK | THE GUARDIAN | THE INDEPENDENT |

| TRADES-UNION- CONGRESS | THE TRUSSELL TRUST | UK PARLIAMENT | UNITE THE UNION |

| UN-WOMEN | WASPI | WIKIPEDIA |

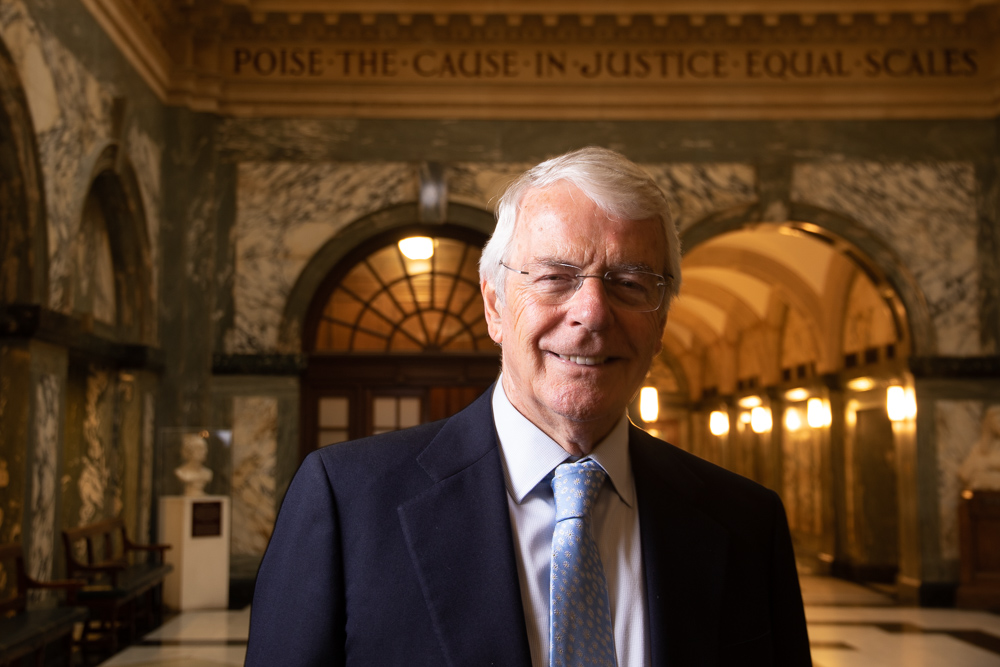

SPEECH BY THE RT HON SIR JOHN MAJOR KG CH, PRISON REFORM TRUST, THE OLD BAILEY – TUESDAY, 9 MAY 2023

Pictured Left – Sir John Major:

“We over-use prison and under value alternative sentences”

The former Prime Minister, Sir John Major delivered a speech at the Old Bailey on 9 May 2023, in which he set out his case for penal reform.

Sir John acknowledged that the problems now being faced within the penal system have intensified over many governments, and that he, his predecessors and his successors should all share responsibility for this.

A copy of his speech is reproduced below.

It’s a great privilege to be here this evening – and in such historic surroundings.

I’d like to thank Alistair King for making it possible – and Edward Garnier for encouraging me to enlarge publicly upon what I have said privately.

Edward – apart from his legal and political career – is a Trustee of the Prison Reform Trust, now Chaired by James Timpson, whose actions match his family’s long concern for prisoner welfare.

The Trust itself, until recently under the guidance of Peter Dawson and now, Pia Sinha has worked for reform with the same persistence as those early campaigners – John Howard and Elizabeth Fry.

I would like this evening, to add a few thoughts of my own.

One of the virtues of age is having the time to reflect on what you have left undone with – no doubt – some regrets along the way. It is such reflections that have brought us together this evening.

I am conscious that, where I criticise, many of the problems are long standing and I, together with predecessors and successors, must each take our share of the blame.

Let me begin with some reassuring news. Violent crime has been falling for nearly 30 years – although the extent of public interest when some horrific crime occurs makes this a deeply held secret for many people.

Despite this long downward trend, legislators have been far more active in framing policy to punish crime than in action to minimise the cause of it.

Many citizens who have faced ‒ or fear facing ‒ serious or violent crime strongly approve. They are clear that they ‒ and their families ‒ are safer if criminals are taken out of society. And, in one sense, they are entirely right.

And yet this instinctive ‒ very human ‒ response ignores the obverse of punishment, which must be rehabilitation.

Stern sentences for violent crimes are necessary, and the instinct to protect the public is laudable ‒ but we should beware that excessive zeal to be tough on crime does not lead us into unwise policy.

We are told “prison works” and – to the extent it holds the worst of criminals in custody, it does – but I do not believe our justice system is well served if it also imprisons those who could better be punished by non-custodial sentences.

Even to use the word “rehabilitation” is taken by many as code for being “soft” on crime; for being gullible; a “do-gooder” who cares more for the villain than the victim

I certainly do not intend it in that sense. Indeed – as I shall argue shortly – I believe such an interpretation ignores the public interest.

When society sends people to prison we are, in reality, “shutting the door after the horse has bolted”: the crime has been committed.

Retribution follows: but, upon release, it is surely in the wider interest of everyone that the crime is never repeated.

That is the purpose of rehabilitation ‒ together with turning around the life of the released prisoner.

If we wish to live under a penal code of which we can be proud, then we must not only punish, but act to reform and re-educate offenders.

I don’t claim that is easy. But I do say that it is sound policy to reduce the risk of re-offending upon release.

We send people to prison ‒ most of them, deservedly, but some not. Either which way, to prison they go. And, to many, that is the end of the matter. Justice is done and the victim has closure.

But ‒ future victims do not have closure if the prisoner re-offends. Prison is at its best when it rehabilitates, and, at its worst if – instead of providing a route out of crime, it provides an education into it.

PRISONERS/EDUCATION

It is instructive to consider the overwhelming characteristics of adults committed to prison:

nearly two-thirds of them have used Class A drugs;

many are illiterate, or innumerate, or both;

almost half have no educational or vocational qualifications whatsoever;

the intellectual assessment of many prisoners equates to that of a primary school pupil.

Two-fifths of those in prison were either expelled or excluded from school; three fifths were frequent truants; many were taken into care as a child; or observed violence in the home; or suffered abuse; sometimes even all of the above.

All of this is a truly wretched preparation for adult life.

We cannot be ignorant of the fact that failures in the early years of life are a serious driver towards crime, and anti-social behaviour.

There is education and training in prison, but its availability ‒ and value ‒ is mixed. After the (Sally) Coates review in 2016 improvements were expected.

Yet, seven years on they have not materialised.

There are reasons.

Poor education contracts; lack of funding; unsavoury prison conditions; and – of course – the impact of Covid, have all stood in the way. As has over-crowding, and the resultant churn of prisoners being moved from prison to prison.

If we wish to attack the causes of crime, better education – in and out of prison – is an essential component.

PRISON POPULATION

Forty years ago, when Willie Whitelaw was Home Secretary, I was a humble Parliament Private Secretary to the two Ministers of State, Tim Renton and Patrick Mayhew.

They were shocked ‒ Willie was apoplectic actually ‒ when the prison population reached 40,000. Today, it is more than double that.

A range of reasons contribute:

our national population has grown;

indeterminate sentences boosted prisoner numbers;

as has legislation increasing terms of imprisonment for many crimes; and

a greater range of misdemeanours may lead to prison.

Comparisons with overseas do not reflect well on our penal policy.

The UK has the highest imprisonment rates in Western Europe ‒ and yet I find it hard to believe we British are uniquely criminal.

So ‒ were our predecessors unduly lenient in sentencing ‒ or are we unduly harsh?

And why ‒ since our prisons are heavily over-crowded ‒ have suspended sentences been declining?

In the year to June 2022, 43,000 people were sentenced to a term in prison. Of these, less than two in every five had committed a violent offence.

Was prison the correct (or fair) sentence for all the 26,000 non-violent offenders? Some, perhaps … but all? I am not sure that it was.

The punishment of prison is to lose liberty, but the prisoner may lose much else besides: their job, their home, their relationships.

That is a high cost ‒ not only for the prisoner, but for society as a whole. The full costs may not be justified.

We might be wise to be more selective.

When prisoners have served their punishment we don’t wish them to be so alienated that ‒ through spleen or necessity ‒ they return to crime. That is in no one’s interest ‒ and especially not the public at large.

Many prisoners ‒ far too many, I believe ‒ are sentenced to short-term imprisonment when other sentences would be preferable. In some cases, care and medical attention are called for rather than prison.

Should the mentally ill be imprisoned, or should they be treated in secure wings of mental hospitals? Surely the latter.

More radically, should non-violent mentally ill prisoners even be the responsibility of the justice department: would not the Department of Health be more appropriate?

I appreciate such a move would not be welcomed by the Health Department, but the Government’s responsibility is to provide the most effective and humane punishment.

Imprisoning people who may be incapable of self-control is simply wrong. They require care, not incarceration.

Of course, mentally ill prisoners who are dangerous or violent must be held securely to protect the public, but they, too, require care as well as custody.

Moreover, should low-level drug offenders ‒ street dealers for example ‒ who are highly likely to be of limited intelligence as well as being addicts themselves – be sentenced to prison, or given an appropriate community sentence?

To be blunt ‒ my suspicion is that many short sentences are pointless and that a non-custodial sentence would be more effective and, perhaps, more fair.

WOMEN

There are over 3,300 women in prison in England and Wales. More than half will serve less than six months. No doubt some are irredeemable, but I suspect most are not.

Over two-thirds of women sent to prison have committed a non-violent crime: at present more are imprisoned for theft alone than for criminal damage, arson, drug offences, possession of weapons, robbery or sexual offences.

I do question whether prison for many of these women does not cause more problems than it solves.

Some have mental problems, or histories of trauma or abuse. Some 50 babies a year are born to women in prison, and reports suggest women in prison are seven times more likely to suffer still birth.

That statistic alone should make us question present policy: whatever the mother may have done, the baby is innocent.

I accept – male or female – we are all equal under the Law, but commonsense and practicality suggests we should look very carefully at community sentence alternatives, before sending vulnerable women offenders to prison.

THE PRISON ESTATE

Reports by HM Inspectors on the state of our prisons do not make for happy reading. Time after time, the conditions of prisons are found to be unsatisfactory. In some they are intolerable.

Many of the old Victorian prisons ‒ Wandsworth, Pentonville, Norwich, among others ‒ were built to hold one prisoner per cell.

150 years later, these cells may hold two – or even three – prisoners, sleeping on bunk beds and essentially ‒ forgive my putting it this way – living in a lavatory.

To have inmates held in worse conditions than in Victorian times is an indictment of policy that is hard to ignore.

Last year, 301 prisoners died in custody ‒ 74 of them by their own hand. This rate of suicide is six times higher than among the general population.

Many suicides are within the early days of custody. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the sheer shock of imprisonment ‒ which, I reiterate, may be for a non-violent crime ‒ is a principal cause of the desperation that leads to self-destruction.

Self-harm in prison has risen by two and a half times over the last decade ‒ most notably by women, but there is also a significant rise in the incidence of male self-harming. I would like to know ‒ why?

I would suggest that prisoners who kill or maim themselves are people in despair – not hardened villains.

f course, the Government knows all this.

In 2015, the Government announced a new prison reform programme to build nine new prisons – and committed £1.3 billion to create 10,000 new prison places by 2020.

This well-meaning plan ‒ let me put it kindly ‒ faltered.

The Public Accounts Committee reported that, despite these pledges, only 206 new places were delivered with 3,500 places still underway.

Meanwhile, prisoners continued to be held in unsafe and over-crowded conditions.

A revised plan followed in 2019 ‒ also to create a further 10,000 places.

This was updated in 2020 when £4 billion was allocated to deliver a total of not 10,000 but 18,000 places ‒ in England and Wales – by the middle of this decade.

The plans included the expansion of four prisons; the completion of building at two more; and refurbishment of the Prison Estate.

Last month, a Parliamentary Question revealed that only 3,100 of that 18,000 target had yet been provided, and only one new prison had been opened in Wellingborough – although I believe a second, Fosse Way, is due to open this year.

Progress? Yes. But 2025 is only two years away, and there is still a very long way to go to turn what was promised into reality.

Prison staffing is an allied and deep-rooted problem.

The turnover of staff is a ruinous 15% a year – which delivers its own message about the job’s lack of appeal, and the toll it must take.

Despite efforts to attract people to become prison officers, there are over 700 fewer officers than there were 12 months ago, and front line staff are 11% below the staffing level of 2010.

This does not suggest a modern prison service is anywhere near delivery.

REMAND

It is said that “Justice delayed is Justice denied”.

And yet, the congestion in our Courts does delay justice.

Consider the remand system.

Remand may be used for accused people before their trial, or those convicted and awaiting a formal sentence for their offence. Within that bland reality lie many complexities, and some injustices.

At present ‒ partly as a result of Covid delays ‒ the number of people on remand is at its highest level for decades: around 14,500.

Typically, two-thirds are awaiting trial, while the remainder are awaiting sentence after conviction.

Of those awaiting trial, one in two are subsequently imprisoned – even though accused of non-violent offences.

Although individual circumstances will differ, I do not believe the case can be made that they should all be jailed.

My belief is reinforced when I learn that – at their trials – one in ten remand prisoners are judged to be innocent of any crime, and a yet higher number are convicted – but sentenced only to a non-custodial sentence.

The need for reform seems evident.

Other factors reinforce that judgement.

Nearly one-third of remand prisoners are held longer than six months before trial, and an unlucky 5% for over two years. That is over 700 remand prisoners held for over two years, before quite possibly being found to be innocent.

They not only lose their liberty but their reputation and their income too, which may well also punish their families. This cannot be acceptable.

Nor is it the fact that, last year over one-third of suicides in custody were by people on remand. I do not think we can be proud of that.

PAROLE BOARD

Parole for prisoners found guilty of serious and violent crimes is inevitably contentious.

In practice, the Parole Board deals only with a minority of prisoners ‒ less than 10% ‒ and decisions “for” or “against” their release or transfer to an “open” prison can be complex and controversial.

Thirty years ago, a House of Commons Select Committee advised that “release should be an entirely judicial decision ‒ independent of the Executive”.

Although this was initially resisted, Parliament did subsequently accept that principle and ‒ in my view ‒ rightly so.

Prisoners also gained the right to present their case for parole to the Board. This ended years of parole decisions taken in secret as a result of evidence that was never challenged.

That was an approach which honoured neither democracy nor equity, and was a blot on our system.

The present more open system does ensure that decisions are taken after a proper presentation of arguments. This seems to have been effective.

One quarter of those considered for release by the Parole Board were successful. Of those, only 1 in every 200 prisoners released re-offended within the next three years.

This would suggest that the Parole Board is not a bunch of gullible “softies”.

Over the years, the Parole Board has evolved from its modest beginnings in the 1960s: with only a handful of Board members, no hearings to consider evidence, and with the final decision being taken by the Home Secretary.

Today, the Board ‒ nominally at least ‒ is independent of Government, and has amassed years of experience and expertise, enabling a level playing field for decisions upon release, without the hype and pressure that would be bound to accompany political involvement.

In the thousands of decisions to be made each year, there is no way that Ministers could possibly match the experience and knowledge of the 350 Parole Board Members.

It is therefore surprising ‒ and worrying ‒ that, over the last year, recommendations by the Parole Board to transfer prisoners to an “open” prison have suddenly, and sharply, been rejected by the Justice Secretary.

In 2021-22 – 94% of the Parole Board recommendations were accepted but, thereafter, that fell to 11%.

It is hard to believe that does not result from an unannounced change of policy that is instituting a harsher regime.

VICTIMS AND PRISONERS’ BILL

The victims of crime have long needed more support than they receive, and there are elements of the proposed Victims and Prisoners’ Bill that are eminently sensible – and long overdue.

As I understand it, the Bill was originally intended to cover the interest of victims only, and the prisoners’ element is a late addition.

I believe this addition is a political misjudgement that may put much needed reforms at risk, and will come to that in a moment.

I welcome the proposal to enshrine the Victims’ Code in Law, which should ensure that greater support is delivered.

But, if theory is to become reality, funding will be needed for specialist support and, thus far, there is no evidence that this will be provided.

I can only hope the Justice Secretary has secured agreement for funding from the Treasury, or the Bill will fail to meet its purpose.

I understand that the former Justice Secretary sought the power to veto decisions made by what is allegedly the independent Parole Board, to release prisoners convicted of serious crimes.

The problem with this is that I do not see how (or why) the Justice Secretary would be able to reach a more just decision than the Parole Board.

Any single Government Minister – however able or well-meaning – would be far more vulnerable to public campaigns and, under pressure, to make a harsher decision to appease them. This is a very slippery slope.

I do not think that any politician should have that power, and I hope the new Justice Secretary will reconsider or – if he does not – that Parliament will deny it.

IPPs

There is one area of the penal code that is over-ripe for action to correct legitimate grievance.

Until 2003, the only indeterminate sentence available to Judges was a life sentence, which was only for the gravest of offences.

But, that year, the Government introduced a new concept: that of indeterminate imprisonment for public protection – so-called IPPs. It was intended for people considered “dangerous”, but whose offence did not justify a life sentence.

It passes a minimum tariff but offers no stated maximum. Release could only be authorised by the Parole Board.

It seems that this scheme went wrong from the outset. It was applied far more widely than expected (or intended), with lower level offenders receiving this harsh sentence.

The number of IPP cases far outstripped expectations, and amendments to the legislation were approved by Parliament in 2008.

But shortcomings remained, and the power to issue IPP sentences was abolished in 2012.

But – and it is a BIG “but”: when it was abolished, no action was taken to determine a just ‒ and definitive ‒ sentence for the prisoners already serving for an indeterminate time.

This was an extraordinary omission, which remains the case eleven years after abolition.

Nearly 3,000 offenders, still imprisoned – including those who have never been released and those recalled back to custody – were sentenced to a minimum term of imprisonment, but not a maximum.

They are all serving sentences that have extended years beyond their minimum tariff and – without Ministerial action – may never end.

This is soul destroying for prisoners and their families, and is emphatically not justice.

I believe that, without any further delay, justice should be served by Government agreement to the Justice Committee’s recommendation of a re-sentencing exercise – backed by the establishment of an expert committee to guide on the practicalities – for everyone still serving an IPP sentence.

I was brought up to believe that we, in Britain had one of – if not the – most just and civilised penal codes in the world. Some of what I have learned in preparing this speech has truly shaken that belief.

People who commit crimes have deservedly forfeited much but ‒ in our country ‒ not, I hope, the right to be treated fairly.

There are many good causes that attract support, and hundreds of thousands of activists plead the case they most care about.

But it is not so easy, or attractive, to plead for people who have committed crimes, and are responsible for their own misfortune. They do not so easily attract sympathy.

Nor, very often, is it politically comfortable for “active” politicians to plead for convicted criminals. In the rough and tumble of politics, compassion and consideration can too easily be derided as “soft” or “weak” – terms which can define as well as defame.

It has ever been thus.

In many ways, it is odd to plead for a more empathetic penal code on the site of Newgate – one of the most notorious prisons in our long national history.

But views evolve.

In pre-Christian days, prisons were not a place of lengthy incarceration but merely of safe custody until a more savage sentence than loss of liberty could be carried out. Those days, thankfully, have gone.

In Saxon times, prison was occasionally used as a means of punishment and – by the 13th Century – to facilitate a sentence of life imprisonment imposed by the Church, which was unable to pass a harsher punishment.

It was when offenders defaulted in payment of a forfeit to the Crown that prison became a convenient inducement to pay ‒ and then became of wider use as a punishment.

I have argued that its use needs to evolve further if it is to become a better instrument to deliver justice and reduce crime.

So, let me summarise my concerns:

We over-use prison and under value alternative sentences;

too many vulnerable people ‒ including the mentally-ill – are jailed;

education and rehabilitation in prison is inadequate;

much of the Prison Estate is out of date and unsuitable;

too many accused are remanded in prison pre-trial;

the Justice Secretary should not remove powers from the Parole Board;

IPP prisoners should be re-sentenced.

These practices, these problems have grown up over many governments.

In my layman’s view, it is time they were addressed – and put right.

ENDS

The Guardian

FOLLOWING ARTICLE FROM THE GUARDIAN – Patrick Butler Social policy editor Sun 30 Apr 2023 20.15 BST

UK households missing out on £19bn a year in unclaimed welfare benefits

Complexity of system and perception of government handouts as ‘shameful’ stopping people from accessing much-needed support.

Millions of UK households are collectively missing out on at least £19bn a year in unclaimed welfare benefits, at a time when many are forced to use food banks or run up debt as they struggle with rising living costs, according to new estimates.

Lower income households are failing to claim benefits and other cash support for which they are eligible, according to a study by the consultancy Policy in Practice. Some families could be forgoing as much as £4,000 a year.

The sheer complexity of the benefits system, lack of public awareness of what support is available for households, and fear of being perceived by others as “benefit scroungers” all contribute to the high level of unclaimed or underclaimed benefits, says the analysis.

It estimates that 1.3m households are eligible for but do not take up the UK’s main working-age benefit, universal credit, resulting in £7.5bn going unclaimed each year. Nearly 3m eligible families do not claim council tax support (£2.9bn), while 5m households miss out on nearly £2bn of support for water, energy and broadband bills.https://interactive.guim.co.uk/charts/embed/apr/2023-04-27-01:47:26/embed.html

“It is shocking that £19bn of benefits and support is unclaimed at any time, let alone during a cost of living crisis,” said Deven Ghelani, director of Policy in Practice. “Missing out on eligible benefits could be the difference between households keeping their heads above water and feeling they are drowning,” he added.

Benefits advisers said they typically secured relatively small additional payments for clients of £10 to £20 a week, which would nonetheless have a transformative effect. “It can mean the family can eat properly, put the heating on, get the bus, take the children swimming – all the things we take for granted,” said one adviser.

But the study found even bigger sums were not unusual. In one case, advisers helped a pensioner couple in Kent living on £280 a week secure an extra £222 a week in pension credit – £11,500 a year. A Coventry pensioner living on £55 a week was found to be eligible for an extra £138 a week (£7,200 a year).

Pensioners are more likely not to apply for benefits on the grounds that they perceive benefit “handouts” to be shameful, say advisers. An estimated 850,000 pensioner households fail to claim £1.8bn annually in pension credit, which is designed to support retired people struggling on low incomes, according to the study.

The government should commit to positive messaging about benefits to ensure claimants are not put off, urged Policy in Practice. “The stigma and shame attached to claiming benefits is a major factor driving no-take-up among those who are eligible but who choose not to engage with the benefit system at all,” the study says.

Millions of lower-income households struggled to stay afloat financially over the past 18 months as energy and food prices soared. Food banks have experienced record demand amid growing food insecurity, with a fifth of households reporting skipping meals, going hungry or not eating for a whole day.

The study argues the social security system has become hugely complex, requiring multiple application mechanisms across different organisations, national and local. Households could easily be required to make six or seven different applications to receive the benefits and cash support they may be eligible for.

“Claimants must become experts in the system’s intricacies and know which hoops to jump through, all while dealing with financial pressure. While some aspects of claim application are unavoidably complicated … the system as a whole needs to avoid adding extra pressure wherever possible,” the study says.

Daphne Hall, vice-chair of the National Association of Welfare Rights Advisers, said claimants needed high levels of confidence, persistence, patience and determination to negotiate benefit systems that can be arduous and put administrative and psychological barriers in the way of applicants in desperate need of support.

The study said that as the value of working-age benefits had eroded in recent years, financially struggling claimants had been forced to locate and navigate a plethora of discretionary emergency support schemes, often administered locally and with differing eligibility requirements.

The £19bn figure does not include the personal independence payment (Pip) and attendance allowance (AA) disability benefits, for which there is no automatic entitlement. If just 10% of Pip and AA went unclaimed, this would amount to £3.5bn annually, the study estimates.

Even when Pip is claimed, some claimants are rejected or receive lower awards after a health assessment. More than two-thirds of those who appeal win their case at tribunal, but nearly half abandon their appeal. A recent report by MPs suggested this was because the lengthy and exhausting appeal process was damaging to their health.

A Department for Work and Pensions spokesperson said: “We are committed to helping vulnerable households and ensuring everyone claims the support they are entitled to. The independent benefit calculators on gov.uk and the free Help to Claim support from Citizens Advice are available to help people check their eligibility and claim universal credit.

“We also regularly promote and raise awareness of the benefits available to the public including through stakeholder support and the Help for Households campaign, with our network of over 600 jobcentres standing ready to help those who need it.” (See PIN – DWP)

Case study: Andy, late 50s, retired teacher

“It was a whole new ballgame,” says ex-teacher Andy, recalling the day 11 years ago when he was told he had multiple sclerosis. He could still work for a while, and claiming disability support was not on his radar. “My mindset was I was not the kind of person who claimed benefits.”

A friend who worked for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) eventually persuaded him to claim employment and support allowance. The form was tricky to complete, and jargon-filled. He didn’t realise at the time, but he had failed to “tick a box”. He got the benefit, but not the amount for which he was eligible.

Years later, by chance, another friend – coincidentally a benefits adviser – checked his award and discovered it did not include a severe disability premium payment he was eligible for. He’d been missing out on £70 a week for years. She made a call to DWP and he was awarded a £14,000 backdated payment.

“I felt like Elon Musk for about 10 minutes,” recalls Andy. The money helped him buy a specialist bed and make essential adjustments to his house. But the biggest effect was it took a great deal of stress out of his life. “I was no longer worried about paying the mortgage or whether I would lose the house.”

The stress returned when the DWP replaced his disability living allowance with Pip and he had to re-apply. Despite his condition having worsened, he was rejected. He applied again twice, unsuccessfully. “I was on the verge of giving up and leaving it for a year because it all became a bit stressful.”

Again with the help of his benefits adviser friend – “insider knowledge!” he quips – he appealed, and this time his claim was allowed. “I’m thankful we have a social security system where we are supported but my God they make it fiddly and daunting and time-consuming,” he says.

“It’s a passive system. They never contact you and say: ‘We notice you are claiming benefit A, did you know you are therefore also eligible for benefits B and C?’ They leave it to you to find out.”

For many people who need benefit support, the “finding out” will be too arduous and confusing a challenge, he says, especially if they cannot call on expert advice to guide them. “Its like they give you an MOT but not a service. I’m grateful for the support but the system is too often crude and impersonal.”

The Guardian

FOLLOWING ARTICLE FROM THE GUARDIAN – Rowena Mason and Aubrey Allegretti Wed 3 May 2023 16.00 BST

Revealed: senior Tory MP was paid £2,000 a month by lobbying firm

A senior Tory MP has been criticised for failing to declare he was paid £2,000 a month to chair a pressure group lobbying Rishi Sunak.

Bim Afolami, a former vice chair of the Conservative party, declared in the register of interests that one of his private clients was a public affairs firm, WPI Strategy. But he did not mention that they were paying him for his work running the Regulatory Reform Group of MPs.

As chair of the group, Afolami has written to the prime minister calling for regulators to be better held to account, and pressed Sunak for change at prime minister’s question time in the House of Commons.

It comes after the former Tory cabinet minister Liam Fox was also criticised for lobbying the prime minister on behalf of a business group that pays him £1,000 an hour.

MPs are in general not permitted to carry out paid lobbying that could deliver financial benefit to clients.

However, Afolami appears to have made use of loopholes allowing parliamentarians to carry out paid advocacy if they are a member of an association that is carrying out the lobbying, or if the work would benefit a sector as a whole rather than a specific company.

Both Afolami and Fox appear to have kept within the rules through these exceptions.

Afolami launched the Regulatory Reform Group, an organisation of MPs, earlier this year, and brought up its work in the Commons in February, without mentioning that he was paid by WPI for his work with the group.

Speaking at prime minister’s questions, Afolami said: “I thank the prime minister for supporting the launch of the new regulatory reform group. Will he commit to working with our group on two specific areas: first, to improve the accountability and responsiveness of our regulators to stakeholders and parliament; and secondly, to improve the economic potential in key growing areas of the economy, such as financial services, artificial intelligence and advanced manufacturing?”

In April, Afolami also launched a report for the group suggesting that a “lack of democratic oversight of regulators is holding back UK productivity and economic growth”, with the author listed as an economist at WPI Strategy, with editorial control from MPs on the group. The report was funded by one of WPI’s clients, Pension Insurance Corporation, which is on the advisory council of the group and contributed a foreword.

Afolami declared on his register of MP’s interests that he is paid £2,000 a month to give “professional advice with respect to property management, mediation services and legal and financial matters” through a family partnership, listing his sole client clients as WPI Strategy. But he did not link this work to his role as chair of the Regulatory Reform Group and acknowledged to the Guardian that he may not have registered his interests correctly.

Labour said it was “yet another report of a Conservative MP leveraging his privileged position in parliament” while being paid by a lobbying company.

“Government policy should be based on what is right for the country,” said Anneliese Dodds, the chair of the Labour party. “Only Labour has a plan to clean up our politics by banning second jobs for MPs once and for all.”

After being asked by the Guardian about his payments from WPI, Afolami said he had contacted the office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards, which advised that he had not registered his role as chair of the Regulatory Reform Group under the correct category of members’ financial interests. “I am in the process of updating the entry, and the entry will be published at the next scheduled opportunity,” he said.

Afolami said: “I spend two days a month in my capacity as chair of the Regulatory Reform Group. This is an independent group of parliamentarians who have come together to improve the overarching regulatory framework in the UK so that it boosts consumer outcomes and UK competitiveness.

“I approached WPI Strategy to help provide secretariat services to the group given their experience in running similar initiatives such as the Covid Recovery Commission. They advised me that Pension Insurance Corporation, an existing client of theirs, would be able to provide some business insight into the project.

“I was keen for the group to produce an initial report, which the Pension Insurance Corporation kindly agreed to support and indeed wrote a foreword to. To be clear, editorial independence was strictly controlled by the parliamentarians.

“Given the time I spent on the project as chair, I asked WPI if they would be willing to contribute to my costs, which they did. I fully declared payment for this. However, for the avoidance of doubt, I have amended my declaration accordingly with the registrar.”

A spokesperson for WPI Strategy said: “We were asked to provide secretariat services for the Regulatory Reform Group including research, project management and communications support.

“Our client, Pension Insurance Corporation (fully declared on the lobbying register), who do a huge amount of work in the purposeful finance space, kindly agreed to fund the RRG’s report and contributed a foreword. To be clear, editorial control rested wholly with the parliamentarians. Bim ended up spending a significant amount of time on the project and asked if we could contribute to his costs, which we agreed to.”

(SEE ABOVE FOR ALL MPs DECLARED SECOND EARNINGS – Westminster Accounts)

© 2023 Citizens2022Committee. All rights reserved.